|

|

British gourmet and writer Fuchsia Dunlop receives the James Beard Award for the fourth time in New York in 2013 for her book, Every Grain of Rice: Simple Chinese Home Cooking. |

A British food writer explains why sensation is important in Chinese food, Yang Yang reports.

Food might be one of the last barriers to fully immerse oneself in a foreign culture, and for British gourmet and writer Fuchsia Dunlop, that frontier for Westerners when it comes to Chinese food is kou gan (mouthfeel), or texture. "Cross it, and you're really inside."

By texture, she particularly refers to that of the food Chinese people are famously interested in, such as goose intestines, ox throat cartilage, chicken feet, sea cucumber or abalone, which Westerners usually consider pointless since they taste like "a bike's inner tube or plastic bags".

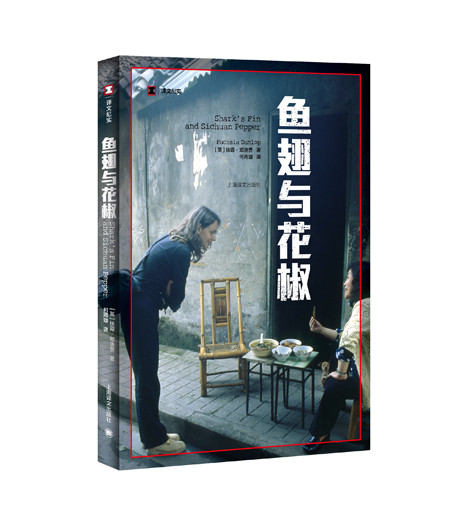

In one of her popular books, Shark's Fin and Sichuan Pepper published in 2008, Dunlop devoted an entire chapter, The Rubber Factor, to what kou gan means in Chinese cuisines.

She lists some representatives: cui of fresh crunchy vegetables (a particular quality of crispness), tan xing (springy elasticity like that of a squid ball), nen (tenderness of just-cooked fish or meat), or shuang (that "evokes a refreshing, bright, slippery, cool sensation in the mouth").

"Actually quite a few readers have written to me and said 'after reading that, we went to a restaurant, we ordered chicken feet, and we tried to eat that differently,'" she says.

In 2016 and 2017, she gave presentations, workshops or gastronomy seminars about texture in New York, Oxford and London. At one seminar in New York, Dunlop prepared a tasting with some jellyfish, a duck tongue, pig ears and so on.

At a food conference in Oxford she gave a presentation about why even the richest people in China would want to eat duck tongue and other foods that in the West are traditionally considered "rubbish eaten by poor farmers". After explaining the texture, she asked all the participants to taste the food.

She asked her audience to put aside their prejudice and negative thoughts, and instead concentrate on the sensation in the mouth.

|

|

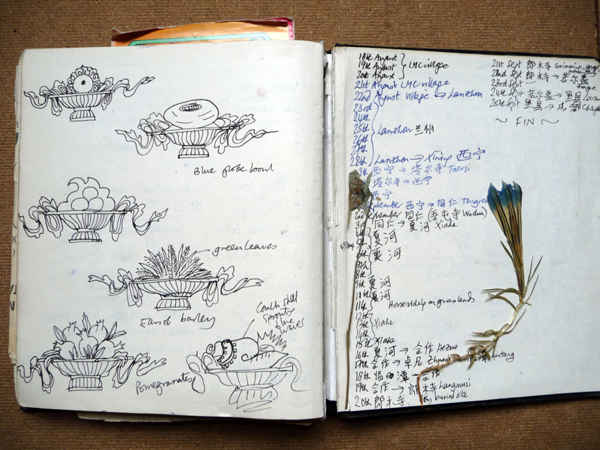

A Dunlop notebook with sketches and notes about recipes of different dishes she has tasted. |

"A lot of people said it was one of the best presentations they'd seen. It was totally fascinating because all these things are new for them," she says.

"They just probably thought duck tongue a bit weird, but they never actually considered why you might want to eat a duck's tongue, so I'm like a kind of missionary for this. I'm trying to get people to open their minds."

She said kou gan enables people to taste a whole range of things like Chinese people.

However, as a woman growing up in Oxford, Dunlop also spent more than a decade to finally cross the last frontier. In Shark's Fin and Sichuan Pepper, she records how she "turns into" a Chinese through adventures with Chinese food and increasing her understanding of its role in society as well as its deep roots in culture.

Now a translation of the book is available on the Chinese mainland.

Dunlop visited China for the first time in the fall of 1992. Although she grew up in a household always filled with exotic flavors-from Japan, Turkey, Spain, India and Austria-and she was brave enough to try unfamiliar food, she struggled to swallow her first preserved duck eggs at a Hong Kong restaurant.

"They leered up at me like the eyeballs of some nightmarish monster, dark and threatening. Their albumens were a filthy, translucent brown, their yolks an oozy black, ringed with a layer of greenish, moldy grey. About them hung a faintly sulfurous haze," she writes.

From Hong Kong, she went to Guangzhou and other parts of China and continued her adventures with local dishes, including the "unexpectedly palatable" stir-fried snake whose "flesh was still edged in reptilian skin".

The preserved duck eggs and other dishes that "made (her) flesh crawl", however, did not cripple Dunlop's interest in the "disorganized" but "vibrant" Chinese mainland in 1992, which she observed was completely different from her imagination.

Returning to London, besides learning Mandarin and writing quarterly roundups of Chinese news for China Now magazine, she also tried Chinese recipes.

In 1993, on her way home from Lhasa, she stopped by Chengdu to visit a friend and ate representative Sichuan dishes such as mapo tofu and yuxiang qiezi (fish-fragrant eggplant) for the first time, which impressed her.

The next year, she got a scholarship to study in Sichuan University for a year. A reason for her to choose Chengdu rather than Beijing or Shanghai was her memory of the food there.

|

|

A Dunlop notebook with sketches and notes about recipes of different dishes she has tasted. |

When she was 11, Dunlop says her dream was to become a cook, but she was laughed at by her teacher. She suppressed her dream until she came to Chengdu. Then, Dunlop studied cooking skills at the Sichuan Institute of Higher Cuisine, becoming one of the first foreign students to learn Chinese cookery.

After her one-year visa in China ended, she managed to prolong her stay to study cookery for another six months. Apparently, the six-day study per week at the school was not enough, so she visited big and small streets in Chengdu to look for delicious food.

Since her teens, Dunlop kept a notebook wherever she went and wrote down the recipes of different dishes she tasted, just like her mother. She has so far used up 130 notebooks.

Returning to Britain in 2001, Dunlop completed her first book Sichuan Cookery, a cookbook called by Observer Food Monthly "one of the top 10 cookbooks of all time".

In 2003, Land of Plenty: A Treasury of Authentic Sichuan Cooking came out, followed by her third recipe book Revolutionary Chinese Cookbook: Recipes from Hunan Province.

After three cookbooks from Sichuan and Hunan, she still had more to say about her experience, so she published Shark's Fin and Sichuan Pepper. In the book, apart from Sichuan and Hunan, she loves Fujian province, where Dunlop gulped down a cup of baijiu (white liquor) mixed with the blood and bile of a wriggling snake, and Gansu province, where she spent a Spring Festival in the village of one of her Chinese classmates and witnessed the Northwest China way of remembering ancestors with food.

After years of exciting but exhausting travels, she discovered the cuisines of Yangzhou, Jiangsu province, where the Huaiyang cuisine represents the taste of Chinese literati.

|

|

The representative Sichuan dish, mapo tofu, cooked by Dunlop. |

In the book, she cites Chinese literati writings about food to show "how deep the roots are of talking about food in China, about considering food as something very important", she says.

"You see that right from the ancient philosophers' using food and cooking as metaphors, and the ideas from The Analects of Confucius. For example, the way you eat is an expression of how civilized you are, and what kind of person you are. It's really fascinating.

"I don't think there's any other culture where food has been taken so seriously, partly because, as I've written in the book, the first duty of the emperors was to feed people. That's the basis of social stability. It's the basis of the home, how you communicate with your ancestors and gods. It's an expression of how cultivated you are."

In 2013, she won the James Beard Award for the fourth time for her book Every Grain of Rice: Simple Chinese Home Cooking. Three years later, Dunlop published her latest book Land of Fish and Rice: Recipes from the Culinary Heart of China.

Dunlop is working on more books and stories about Chinese food and culture, given the huge diversity of cuisines in China.

Contact the writer at yangyangs@chinadaily.com.

|

|

Fuchsia Dunlop prepares Chinese homemade dishes. |

|

|

Dunlop cooks at the Sichuan Institute of Higher Cuisine. |

Presented by Chinadaily.com.cn Registration Number: 10023870-7

Copyright © Ministry of Culture, P.R.China. All rights reserved